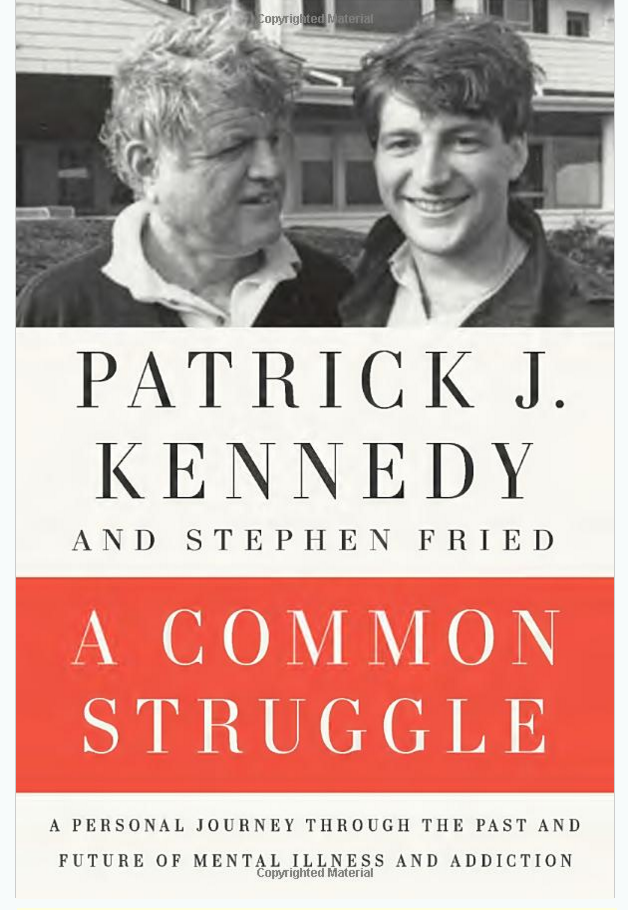

A Common Struggle: A personal Journey through the Past and Future Mental Illness and Addiction by Patrick J. Kennedy and Stephen Fried

A Common Struggle: A personal Journey through the Past and Future Mental Illness and Addiction By: Patrick J. Kennedy and Stephen Fried

A Common Struggle: A personal Journey through the Past and Future Mental Illness and Addiction By: Patrick J. Kennedy and Stephen Fried

This is a story, told in the first person of Patrick J. Kennedy. It is really two stories presented to us simultaneously. It is about Patrick Kennedy, son of Edward Kennedy and nephew of JFK and Bobby Kennedy. He has been a US congressman from Rhode Island for eight terms and was one of the staunch advocates for parity legislation, for mental illness, and addiction. Yet at the same time that he was leading the fight in the United States Congress to bring about these major changes in our healthcare system, he himself was secretly battling mental illness and addiction.

An important part of his personal story was a discussion of alcoholism in his family. Not only was the author an alcoholic but his brother, mother, and father, Ted Kennedy also struggled with this condition. It is significant that all of them except his father ultimately recognized their problem and entered various programs to help themselves. His mother battled alcoholism for a prolonged period of time and yet her condition was not recognized by family members despite the fact that they knew about several hospitalizations and treatment programs that she had undergone.

One of the most revealing insights about his father that he revealed in this book is how Ted Kennedy was traumatized by the tragic death of his three brothers, JFK, Bobby Kennedy, and his oldest brother, Joe Jr., who was killed in World War II. An additional major trauma for Ted Kennedy was the death of the young woman in Chappaquiddick, an incident well covered by the press.

It was not a simple pathway for the author to recognize his own problems. Even after a period of therapy with Psychiatrist Peter Kramer, author of the well known book (Listening to Prozac). Kennedy felt this treatment was helpful but did not eliminate his addiction problem or allow full acceptance of his bipolar condition. He vividly described how he would convince himself that he didn’t have any problems if he didn’t drink in public or take “illegal” drugs.

Patrick Kennedy served in the Rhode Island legislature and was elected as the youngest member of the US Congress in 2004 during a period that his addiction and mental illness was hidden from the public. It was also pretty much hidden from himself.

His colleagues in the US Congress ultimately became aware of his attempts to hide his drinking problem. Kennedy describes an important event for him when in 1996, Minority Leader, Dick Gephardt, offered him the prestigious chairmanship of the Congressional Campaign Committee on the condition that he stop drinking. This made him realize how he was denying that he had a problem that was known to others.

It wasn’t until 2005 that he publicly admitted that he was suffering from a mood disorder that was being treated by a psychiatrist. While his own struggle continued, he became more effective in his advocacy in the US Congress. One misconception he believed had to be clarified concerned Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign against drugs. He felt that this missed the main point that addiction is not something you can simply say no to, just as you can’t say no to cancer. It is a disease and by implying you can just say no stigmatized people who have the genetic propensity to have this disease.

As much as the story of Kennedy’s recognition of his own illness of addiction and mental disease and how he battled it is quite enlightening, the battle for a definitive bill in the US Congress is just as revealing.The events leading up to the 2008 Wellstone and Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act are quite interesting and complicated. They are also quite personal to Patrick Kennedy. It took place at the time that he was relapsing to alcohol and painkillers and also was having an exacerbation of his bipolar condition. While Patrick Kennedy was one of the leading champions in the House of Representatives for this legislation, his father, Ted Kennedy, was a major supporter of this bill in the US Senate. This was also at a time that the senior Kennedy was dying of a brain tumor. Compromises had to be made in the bill and the Senate was reluctant for the legislation to be as comprehensive in various aspects and details of the bill as was wanted by the House of Representatives. There also was a question how the legislation would deal with the new surge of mental health problems occurring in soldiers returning from the war. There was a concern that it should cover PTSD as well as addiction in the returning servicemen. Patrick Kennedy described the dramatic moment that his dying father came to the senate floor to vote for the final version of the bill to the applause of the US Senate.

Even with the passage of this extraordinary legislation, the battle for adequate parity for healthcare support was far from over. The proof and the success of this landmark bill would depend on the implementation by the federal and state governments and certain local rulings are expected to eventually reach the Supreme Court. The 2016 presidential race can certainly also be expected to impact the success of implementation of this legislation. As of this writing, it appears that the Republican candidates may be reluctant to support the implementation of this legislation and provide funding for new programs.

Patrick Kennedy decided to leave the United States Congress in 2010. Since departing from Congress, he has continued to be a leading advocate to bring about implementation of the 2008 legislation for mental illness and addiction. In this regard, among many other things, he has worked with two important organizations in which he plays very active roles. The Kennedy Forum (kennedyforum.org) gathers experts in mental health and addiction and holds important conferences that they hope will ensure implementation of the 2008 legislation. They are also committed to promoting a translation of neuroscience into the preventative and treatment interventions for mental health and addiction. The second organization in which Patrick Kennedy is involved is One Mind (onemind.org), which is dedicated to the promotion and support of “brain health” and creating a fast track for treatment. Their current focus is on new approaches to treat and cure PTSD but they look forward to applying solutions for all brain disease including depression, Parkinsons, ALS, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and addictions.

Patrick Kennedy does not bemoan problems. He is clearly a man not only with a vision but with plans and solutions. He concluded his book with a scorecard of how we should rate our public officials who have the opportunity to pass legislation and make changes. Also at the end of the book, he had a section for people who are dealing with their own mental illness and addiction. He tells them not to be alone in this struggle and how important it is to get treatment. Finally, sandwiched in this book was a series of photographs of many well known members of his family. It brought back many memories to this reader of the great accomplishments of many members of the Kennedy family and of the tragic events that they experienced.

It should be noted that at the time that Patrick Kennedy wrote this book, he was three and a half years sober. He has shown that he is a very accomplished and insightful man. I believe we are going to hear a great deal about him in his advocacy. He has provided in this book a valuable historical account of the reasons to fight for the proper care of mental illness and addiction. I am sure he has a bright future and many people will benefit by his skills and his passion.

Comment » | AM - Autobiography or Memoir, MHP - Mental Health/Psychiatry, P - Political

Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry by Mary Ann Cohen, Harold W. Goforth, Joseph Z. Lux, Sharon M. Batista, Sami Khalife, Kelly L. Cozza and Jocelyn Soffer, Oxford University Press, New York, 2010, 384pp, $49.95

Handbook of AIDS Psychiatry by Mary Ann Cohen, Harold W. Goforth, Joseph Z. Lux, Sharon M. Batista, Sami Khalife, Kelly L. Cozza and Jocelyn Soffer, Oxford University Press, New York, 2010, 384pp, $49.95